Are You Training in the “Gray Zone”?

Are you putting in junk miles, risking injury or stifling your performance by training too much in the gray zone?

The world of endurance sports is growing at a massive clip. Every day there are more people donning their running shoes, bike helmets, hiking boots and/or swim goggles. Outdoor physical fitness is booming; it’s an exciting time to be a part of these sports.

As a coach with more than 20 years experience, I’ve seen my fair share of training tactics and strategies. But there are two fundamental responsibilities that every coach assumes for their athletes: enhance their physical fitness levels and help them avoid injury.

For those taking on endurance sports without the help of a coach, my advice is to find a training program that will adhere to the above. New and inexperienced athletes tend to over do it in training. The need to “get in a good workout” or “work up a good sweat” can get in the way of executing a well balanced training program. They go out too hard and put forth an effort that feels sustainable but may ultimately lead to injury. This is what we call training in the gray zone.

Polarized training

To understand what the gray zone is, it’s important to have an understanding of the general structures of endurance training.

The most popular and scientifically researched training is polarized training.

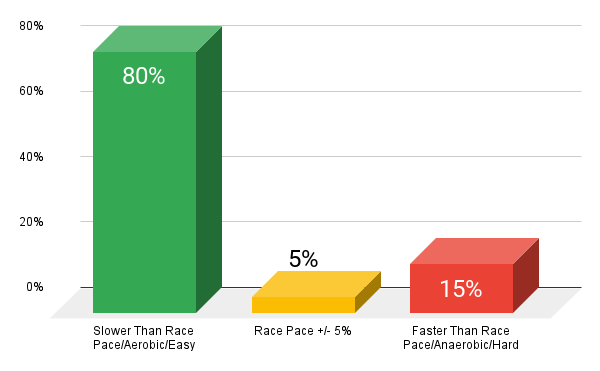

Here an athlete splits their efforts; some workouts are intended to be easy, and others are intended to be hard. Very little time is spent in the middle.

Stephen Seiller may be the most well known supporter of polarized training. Seiller simplified training into three zones (Z1-3), suggesting athletes should spend most of their training time in the easy zone (Z1), a little time training hard (Z3) and virtually no time in the middle (Z2).

In 2014, Mat Fitzgerald coined the term 80/20 training in his book 80/20 Running under the guidance that 80 percent of an athlete’s training should be easy and only 20 percent should be hard.

How and why does polarized training work?

This method elicits a predictable response from the body. In a very oversimplified explanation, the body of an athlete needs to transfer oxygen to muscles → oxygen is used to create fuel → fuel is used to activate muscles and generate movement.

This is all developed through various segments of training.

Getting oxygen to muscles to create fuel is the “engine” of an athlete, commonly referred to as the aerobic base. There are two primary components involved, capillaries and mitochondria.

The amount of oxygen you can transfer is dependent on the size of your capillaries. The larger you can make them, the more oxygen you are able to transfer. The rate at which you can use that oxygen is dependent upon how developed your mitochondria are. Just like working out a muscle to get stronger, mitochondria can be trained to use oxygen more efficiently.

It’s been proven that both of those components develop at the highest rate when larger volumes of lower intensity training are applied. The more time spent moving at Z1 creates the perfect environment for your aerobic base to grow.

The last part of the equation is where the harder intensity work comes into play. The amount of movement your muscles can create is dependent upon how strong they are and how long they can maintain an effort. This is often referred to as muscular endurance or racing economy.

Higher intensity efforts are proven to work best when trying to develop your muscles. This is where Z3, or that 20 percent, comes into play.

The combination of the above will help athletes obtain the greatest amount of gains with the lowest level of injury risk. On easy days stay easy. Don’t drift into the gray zone. It could lead to under performing on race day or worse.

The gray zone

With the easy/Z1 and hard/Z3 defined as our primary focus areas, the gray zone is the middle area/Z2. It is a moderate effort that is too hard to get the benefits of easy efforts in your aerobic base and too easy to get the benefits of hard training for your muscular endurance/economy.

Spending time in this zone is also referred to as ‘junk miles’ because the effort put in does not generate a high return in performance.

In addition, spending a lot of time in this zone is wasted effort. The harder the effort, the longer the recovery time, and many athletes are already under-recovered from the previous day’s training. This compounding effect leads to overtraining, burnout and injury.

Are there exceptions to the gray zone rule?

In some long distance triathlon training as well as marathon running, athletes may train in the gray zone during segments of race pace training. However, these are race prep specific workouts and would only comprise a small percentage of training.

Another popular training method, predominantly among cyclists, is called sweet spot training (SST). Here a cyclist would execute workouts that are approximately 80 to 90 percent of their threshold power, which falls into the gray zone. However, this training approach is also coupled with a balance of easy volume as well.

***

Mike Trees is a running/triathlon coach (NRG Coaching) and all around elite endurance athlete. As a runner, Mike competed at Britain’s top sports University, Loughborough. He went on to race and coach all over the world, most recently in Japan. After 15 years racing as a professional triathlete, Mike eventually took up coaching triathlon and has coached Olympians and world champions, as well as National level and top amateurs.